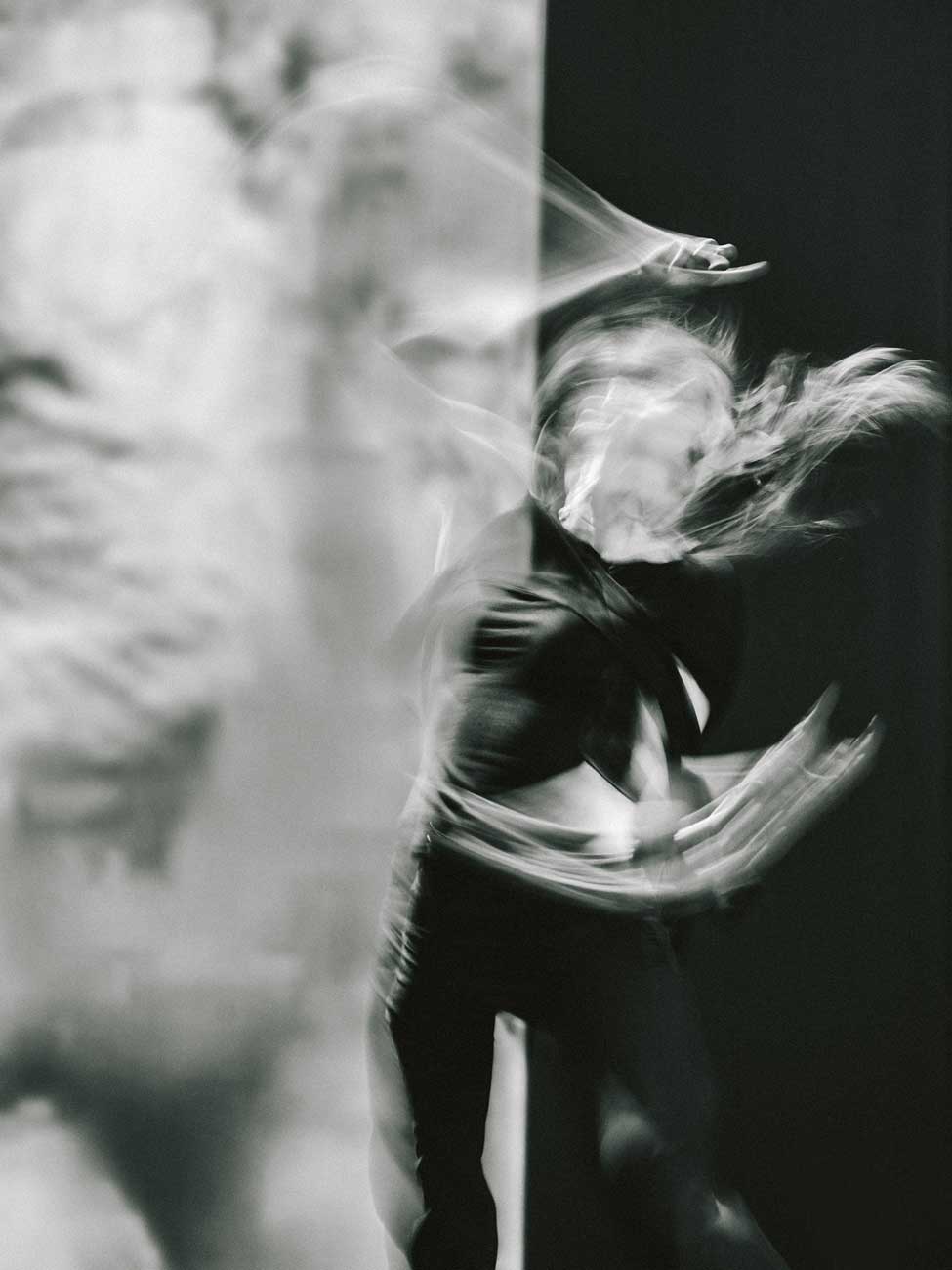

“The Last Days of Mankind” is an international theater project, which the Teatr A Part co-produced with Theaterlabor Bielefeld from Germany according to the antiwar satirical drama of Austrian writer Karl Kraus, documenting the horrors and absurdities of the First World War . This text, considered to be the longest drama in the world, has been adapted in the performance to the form of the spectacle, which is a dynamic collage of various theatrical styles. The drama’s text is given in a performance alternately in several European languages (languages of the artists appearing in it: English, French, German, Polish, Portuguese, Russian, Serbian, Scottish and Ukrainian), which makes the show a real theatrical tower of Babel.

The play, jointly directed by Yuri Birte Anderson, Marcin Herich and Siegmar Schröder, includes artistic groups from seven countries: Theaterlabor Bilelefeld from Germany, the Scottish Leith Theater, the Serbian theater Plavo Pozoriste, the Media Culture Association from Ukraine, the Association Arsène from France and the Teatr A Part. The music for the performance was composed by the famous English musical cabaret The Tiger Lillies, who plays in the performance live.

The performance took place on 8 and 9 June 2019 in the theater and cinema hall of the Youth Palace in Katowice as part of the 25th International Performing Arts Festival A Part.

Presentations of “The Last Days of Mankind” in Katowice is the second vison of the spectacle. The first, directed by Yuri Birte Anderson and John Paul McGroarty, in collaboration with Marcin Herich and Siegmar Schröder, took place last November at the Leith Theater in Edinburgh on the centenary of the end of the First World War (six presentations).

The third, final edition took place in Bielefeld, Germany in October 2019 (three presentations).

“Last Days of Mankind” is part of the “Cafe Europa” project, carried out by Theaterlabor Bielefeld in cooperation with the Leith Theater in Edinburgh, Association Arsène from France and the Teatr A Part with the support of the European Commission under the Creative Europe program.

scripts and drection: Yuri Brite Anderson, Marcin Herich, Siegmar Schröder

video: Odile Derbelley, Michel Jacquelin

music, lyrics: Martyn Jacques

translation: Jacek Katański, Kaja Katańska

performers: Thomas Behrend, Michael Grunert, Janet De Vigne, Odile Derbelley, Michel Jacquelin, Hanna Kryvsha, Cezary Kruszyna, Natalia Kruszyna, Martin MacLennan, Sophia McIean, Jelena Martyinovic, Freya Muller, Carolin Ott, Katryna Ponomarenko, Marko Potkonjak, Isabel Remer , Anton Romanov, Dejan Stojkovic, Alina Tinnefeld, Paul Tinto, Monika Wachowicz and The Tiger Lillies (Martyn Jacques, Andrian Stout, Jonas Golland)

duration of the performance: 1 hour 30 minutes

REVIEWS

Body, history, identity

Images disappear. Bilder verschwinden. Les images disparaissent. This is important enough to be repeated in several languages. We hear it in the final of the performance, and the words are finally spoken seriously. Even with fear. And a few minutes earlier, Michael Grunert, actor Theaterlabor Bielefeld, who plays for us, the viewers, the only historically recognizable character – Karl Kraus – will say something that will be repeated by another writer, essayist and playwright, Imre Kertesz. That we would forget who fought this war, when and why; and that we forget it will happen again. Europe waited only two decades for the fulfillment of Karl Kraus’ prophecy. So much was one great war from the other. But of course the threat is still in force, because we have not worked through the lessons of the Great War or Auschwitz (Kertesz). If today in Europe you can go back to ideas that led you straight to the apocalypse, it means that nothing has changed. And that’s why, perhaps, artists from this Europe (German Theaterlabor Bielefeld, Serbian Plavo Pozoriste, Scottish Leith Theater, Ukrainian Media Culture, French Association Arsene, and Polish Teatr A Part) reach for the anti-war arsenal, the eight-page dramatic record of war horror that are the “The Last Days of Mankind” by Karl Kraus. It is worth noting that this is the second attempt at staging in the country since the translation of Kraus’s work into Polish (Jacek Buras).

Piotr Cieślak’s performance was directed at the Teatr Powszechny in Warsaw in 1997. It is said that if the entire eight hundred pages were put on the stage, the staging would have to take 24 hours a day, so the subject could be interested in the theater marathon specialist Krystian Lupa, but he was not interested. It is also said that the obvious difficulty of this dramatic material is not quantity but quality. Everything, almost every picture, every issue spoken out, have power and seem equally important. Cuts, however, cannot be avoided. The directors of theatrical cooperation compressed the art for less than two hours and created a fully audiovisual spectacle that has its obvious advantages. Disadvantages, unfortunately, too. Certainly the visual bombardment – the screen in the background of the stage, the text of the translation displayed under the ceiling, the viewing angle extended to 180, and even above 200 degrees (the action of the art too often forced me to look sideways, and even behind my own back) – it is not used for focusing comments. It is basically a simple recipe for disaster. If the intention of the creators was to create an impression of chaos, to lift the stage boundary (a topic that has been pushed through by the festival for years), to break through force (for which war and the media reporting it) into the intimate space of the observer and threaten it, this is partly a procedure succeeded (advantage). But I am not able to assess the scale of losses in relation to the scenes, actions, issues spoken at the same time in another part of the theatrical space.

“The Last Days of Mankind” are told with passion – which cannot be said of Cieślak’s traditional and sluggish staging. We don’t have talking heads here, only constant activity within the word and the stage movement, we basically participate in some apocalyptic, verbal and bodily convulsions generated by war experience (and awareness of the end of history). All portrayed social groups and actors presenting them are subject to this law of convulsions, galloping entropy. Even Karl Kraus himself, who in the archival material displayed on the screen recites the text “Last Days of Mankind”. This language (above all body language) we know from somewhere, it resembles another spectacle taking place in most of the Nazi stands. I don’t know if this is the intended effect. Or maybe the very character of Kraus was absorbed in chaos (and the method used by the creators of the performance). Many commentators on the work of the Austrian playwright have repeated that what saves the eight hundred-page record of war horrors, which, by the way, does not include only accounts of trenches, but above all the perception of war by society, is irony. Quite seriously, you couldn’t just bear it. And here we reach the essence of the performance. “The Last Days of Mankind” are the work of international theater cooperation, but they probably have the strongest aesthetics of Teatr A Part.

If we recall “Bellmer Circus” and “In the Jungle of History. Variete” (the performance, also realized in cooperation with Theaterlabor Bielefeld, as you can see, was a preparation for staging Kraus’s art), we will immediately recognize the stylistic and genological codes. Oneiric-allegorical tale as if taken from the clinic of Dr. Gotard – another Schulzian demiurgos who is trying to revive time “with all its possibilities”, saturated with cabaret, decadent tradition (which in “The Last Days of Humanity” watched phenomenal musicians from The Tiger Lillies). We recognize masks and their names, cheap, fair props, a skillfully controlled border between seriousness and kitsch, and finally human weaknesses and perversions – our true face to which (culture as a source of suffering) we constantly sigh, and which we secretly miss.

Radek Kobierski, “Śląsk” no. 8/2019

The jubilee edition of the festival began with a fantastic concert of the British formation The Tiger Lilies. The characteristic, hoarse falsetto of the band’s leader, Martyn Jacques, accompanied by an unusual instrumentation, filled the interior of the Rialto Theatre full of spectators with stories about life in the underworld, full of sadness, atrocities and addictions. Brecht’s cabaret tradition, grotesque and black humor, so characteristic of this musical formation, came back with even more powerful force two days later, as part of the monumental production of “The Last Days of Mankind”. Last year, on the centenary of the end of World War I, directors: Yuri Birt Anderson, Marcin Herich and Siegmar Schröder created a total and uncompromising spectacle in which artistic groups from seven countries take part: Theaterlabor Bielefeld from Germany, Scottish Leith Theater, Serbian Plavo Pozoriste, Media Culture Association from Ukraine, Association Arsène from France and Polish Teatr A Part. The Tiger Lillies plays songs here live, which Jacques composed especially for this production. The directors reached for the anti-war satirical drama by Karl Kraus, translating the 800-page song into an extremely dynamic visual-music-language collage. The accumulation of foreign-language dialogues, often conducted polyphonic and crazy visual structure, which consists of the actors’ play in different places of the hall simultaneously (stage, loggias, back of the room behind the back of the audience) and the content displayed on the screen located in the background of the stage (archival, drastic photos from the war) interrupted by live broadcast from a camera, whose operator is one of the actors) form a real theatrical tower of Babel. But there is a method in this macabre-grotesque madness. The viewer is brutally drawn into the middle of events, aggressive stimuli raise the pulse, print drastic images under our eyelids. How long will these afterimages last? According to Kraus, we quickly forget who and for what reason was at war, how many people died, how low humanity fell. Images disappear.

Aneta Zasucha, “Scena” no. 3-4/2019

Photos: Maciej Dziaczko

open gallery view video